How can the Tenure Guidelines be used to regulate the housing market?

The financially focused solution to the 2008 economic crisis created a reality in which families cannot afford to buy a house, nor to pay the rent. In Barcelona, 42.7% of the population spends more than half of their salary on housing. While 20% of workers earned equal or less than the minimum wage in 2020 (935€/month), a 70 m2 flat in Barcelona costs on average 1050€/month.

In the meantime, empty houses remain in the hands of investment funds, the Spanish banking system and large-scale landlords, thus promoting the financialization of urban housing and the gentrification of entire neighborhoods. 73% of the properties owned by corporations are empty. The only option for some people is to occupy these empty houses, but these people are also being evicted. Housing has become an investment asset, instead of a right for all people. The market has not regulated itself, but rather it has spurred more speculation.

Irene waits in her house for the eviction to happen with her things packed / Bruna Casas – RUIDO Photo

The Tenure Guidelines urge states to prevent uncompetitive practices that enable equal participation, regulate markets, protect the right to tenure of vulnerable groups, prevent land speculation and concentration, and ensure market transparency (Articles 11.2 & 11.3). The TG are relevant in the urban context because they make clear that unregulated markets and uncompetitive practices seriously threaten the right to land, and therefore, housing, for vulnerable groups. These guidelines recognize cultural and social values which are “not always well served by unregulated markets” and provide a rights-based framework in which land and housing are understood as rights, and not as investment assets.

As we have seen, the Spanish government approved laws that exacerbated tenants’ vulnerability to abuse by powerful landlords and the financial system, rather than protecting them. However, since 2013, social mobilization led by newly formed groups advocating for the right to housing, such as Sindicat de Llogaters or PAH (Platform of People Affected by Mortgages), have started to make some progress. In 2013, a Popular Legislative Initiative (ILP) promoted by PAH urged the Spanish Congress to take urgent measures to protect debtors.

Although this law (1/2013) was approved and included debt restructuring and promotion of social housing, it did not provide for payment in lieu (which allows debtors to surrender their property to settle a mortgage debt) or mortgage cancellation in case of abusive clauses. This last right has been acknowledged by the European Court of Justice in 2022. And nevertheless, the availability of social housing continues to be extremely limited: at 2.7% of housing stock compared to the European average of 15%.

In July 2015, the Parliament of Catalonia approved the “Catalan law against evictions” (Law 24/2015) based on a Popular Legislative Initiative (ILP) that collected more than 150,000 signatures. Its main measure was the introduction of a mandatory offer of social rent before eviction that only affects those evictions promoted by large landlords. Although it has been challenged on different occasions, the law is currently still in force.

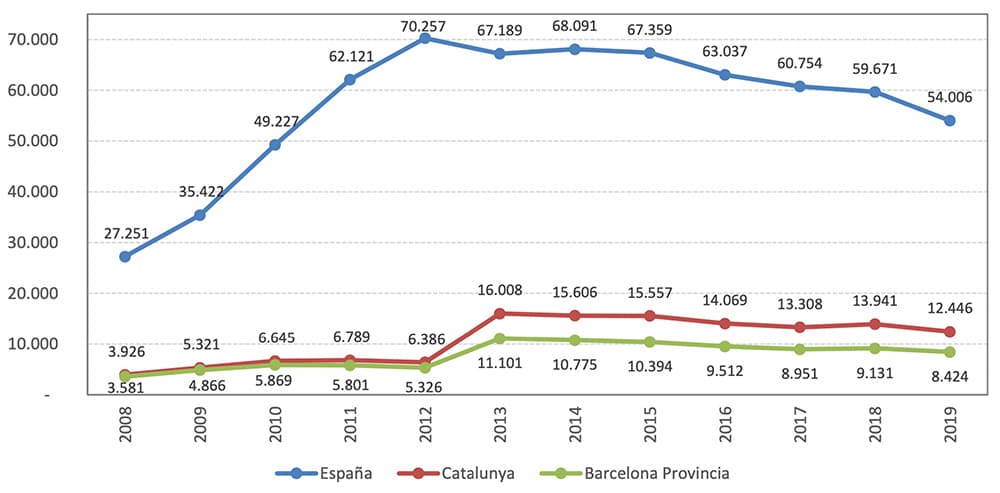

In September 2020, the Catalonian regional government passed a law promoted by Sindicat de Llogaters with the support of 4,000 other social organizations to limit rent prices in areas of market speculation. The objective of the law was to ensure that no one would have to spend more than 30% of their salary on housing. After a year and a half of successful implementation —which led to a 5.5% decrease in rent prices—, the Spanish Constitutional Court declared the law unconstitutional stating that the Catalan government had no competence in market regulation. However, this contentious decision needs to be understood within the context of Catalonia’s on-going fight for independence. Although the Spanish government is drafting a new law to regulate the housing market, social organizations fear that, once again, the law will be watered down.

The Tenure Guidelines are relevant in the urban context because they make clear that unregulated markets and uncompetitive practices seriously threaten the rights of vulnerable groups

Block Ruth, an occupied house in Barcelona where people that has been evicted live / Bruna Casas – RUIDO Photo

This article has been possible thanks to the work and support of RUIDO Photo and Observatori DESC.