Sumalo peasants fight for their right to land

The struggle of Sumalo peasants for their right to land began in 1979, when the Litton family acquired the 214 hectares of land they were occupying by paying a measly sum to the government of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, which signaled a green light to title reconstitution. In 1988, the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) was implemented in the Philippines: one of the largest land redistribution programs in the world designed to counter the social, political, and economic inequalities in the Philippine countryside. Thus, the peasants of Sumalo turned to the government promises of agrarian reform to contest the Littons’ property claims.

However, in 1995, the government announced the establishment of the Bataan Ecozone, a Special Economic Zone that would allow this land to be used for industrial purposes. With the new possibility of industrial development, the Littons began a legal battle against the peasants. The Littons filed for an exemption from the CARP and petitioned for land use conversion. These proceedings lasted over a decade, until 2007 when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Littons.

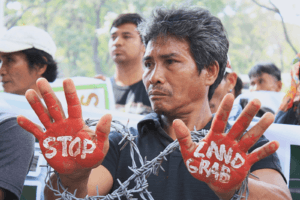

With this legal backing, the Littons, now operating under Riverforest Development Corporation (RDC), began fencing in parcels of farmland and installing private armed security to forbid peasants from accessing their land. Deprived of their source of livelihood, some peasants left the region. Others stayed, but resisting meant facing continuous threats, physical abuse, harassment, coercion, forced evictions, and other human rights violations.

To whittle away at the peasants’ resistance, Riverforest also utilized legal tactics to criminalize peasants. Up until now, the Littons have filed more than 50 criminal cases against peasant leaders with a range of accusations: from minor charges such as unjust vexation, verbal abuse, trespassing, and theft (allegedly occurring when peasants harvested agricultural produce), to trumped-up criminal charges such as kidnapping, destruction of private property, and illegal possession of firearms. Several leaders who also worked as local government officials were charged with administrative offences such as grave misconduct, corruption, and abuse of authority. These incidents led to the arrest and detainment of key leaders of the movement. It also perpetuated an endless cycle of fear and intimidation in the community.

José Laysa experienced harassment for trying to enter his farm / Focus on the Global South

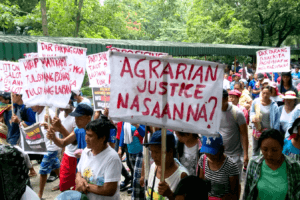

Given this ongoing conflict, Riverforest was unable to introduce any substantial developments in the area. According to the rules for land conversion, such a failure may cause a landholding to be subjected to Compulsory Acquisition under CARP. Thus, in 2013, the peasants of Sumalo, now organized under the Organization of United Farmers and Residents in Barangay Sumalo (SANAMABASU) filed a petition for agrarian reform coverage. In 2019, The Office of the President (OP) ruled in favor of the peasants’ claims.

Once again Riverforest responded with criminalization, intimidation, and harassment. In 2019, a young farmer leader was shot to death during an altercation with one of Riverforest’s guards. The company also took advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic to establish more checkpoints, thereby further constricting people’s movement. The company also enacted a traditional and social media strategy using their personal connections to change the narrative of the conflict and harass leaders through social media trolls.

New spurious criminal charges were filed against key movement leaders. The company also managed to obtain a favorable decision from local courts to eject farming families from their residential lots in the area, claiming that the OP decision only covers agricultural land and not residential areas. In May 2021, Riverforest demolished several houses in the area under a court order.

Then another violent demolition of 53 houses took place in October 2022, displacing 73 families and ejecting duly identified agrarian reform beneficiaries. Several community members, including those who resisted the demolition, were hurt by Riverforest’s private guards. SANAMABASU stresses that this was a strategic move by Riverforest to stifle the community’s land claims based on the agrarian reform.

Finally, the Department of Agriculture Reform (DAR) processed the government titles for the entire 214-hectares following the OP decision in favor of agrarian reform coverage and negating Riverforest’s legal claims over the land. Despite this victory, the Sumalo peasants continue to be criminalized and fear reigns in the community while the state does not guarantee the peasants’ most basic human rights.

In July 2022, nine peasant leaders, eight of them women and four of them elderly, were charged with syndicated estafa, punished with life imprisonment. On 21 February, 2023, the authorities issued the warrant arrests, forcing them to temporarily evacuate their homes. Finally, on 8 March, the International Women’s Day, the peasant leaders decided to “surrender” to the authorities to assert their legitimate claim to the land.

To whittle away at the peasants’ resistance, Riverforest utilized all kind of tactics to criminalize peasants, from harassment and coercion to trumped-up criminal charges

Riverforest Corporation Development / Focus on the Global South