Ukrainian peasants are not only dealing with damages caused by war; they are also under pressure from corporations hungry to control Ukraine’s productive land

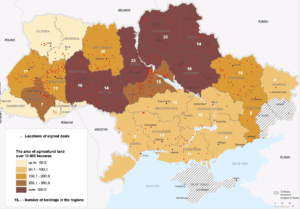

Ukrainian farmers are bearing the brunt of the war: as one of the world’s top grain producers for export, the farming industry is facing damages to key infrastructure caused by the conflict. Meanwhile, peasants are resisting the Russian invasion while continuing to feed the population as bombs are being dropped. What’s more, the war has revealed structural failures in food systems and land distribution. Since 2008, Ukraine has been targeted by speculators. At present agroholdings control 29% of the country’s agricultural land and most foreign investors have their companies registered in tax havens. War and conflict can create opportunity for investors as land is abandoned, property certificates stolen, and the war-torn country finds itself in need of foreign capital to recover. Therefore, during reconstruction, regulating and controlling the land market to prevent further land concentration will be critical. The Tenure Guidelines can serve as a key tool in this regard, as they can also help lay the groundwork for a transition to just and equitable land distribution and food systems.

Across Ukraine, breadbasket of Europe and the world, farmers are bearing the brunt of the Russian invasion: suffering devastating consequences in their fields and some fighting on the frontlines. Wheat fields are being burned, farms occupied, equipment stolen or damaged, silos and refineries blown up, crops seized, property seized, roads and ports blocked, and farmers accused of being spies. Some farmers have lost their sons, family, and friends. Others have had no choice but to flee, leaving their land and farms behind to save their lives, like Yevguén and his family.

Peasants who have stayed behind in Ukraine face obstacles to collect this year’s harvest, and most of it has been severely compromised. Around 30% of arable land will be impossible to harvest this season because it is littered with rockets, munition, and artillery. Estimates suggest that it will take five to eight years to demine the affected areas, but the problem is if this land will be safe again for growing food in the next years or decades. Moreover, the war will have an enduring impact on the environment. As of beginning of November 2022, NGO Ecoaction has documented 685 acts of aggression that pose potential risks of negative environmental effects, such as damages to nuclear power plants and hazardous waste storage facilities that can cause chemical pollution, along with other potential problems.

How the conservation and recultivation will take place will be a key issue after the war. Farmers question whether the loss will be compensated by supporting farmer’s families and through a land redistribution reform. There is the risk to convert other regions of the country into arable land in a territory where the percentage of land for agriculture is already far from reasonable in terms of agro-ecological balance.

Around 30% of arable land will be impossible to harvest because it is full of ammunition, but the question is if this land will be safe again for growing food

Oleksandr Ratushniak / UNDP Ukraine

Farmers are also having problems buying fertilizers and gas for equipment and shipping their products to market, especially for export, while the price of grain on the local and national market is considerably lower than the one for export. Many farmers will lose their investments from this entire year. Peasants in occupied Ukraine are forced to collect and sell their crops to Russian troops at exceptionally low prices and some feel pressured to negotiate with the occupiers to survive. There have also been reported cases of stolen grain in occupied territories. Other farmers, however, tirelessly resist the Russian invasion and work in the shadows, amidst bombs, to continue feeding the Ukrainian population. Before the war small farmers grew as much as 98% of the country’s total potato harvest, 86% of vegetables, 85% of fruits, and 81% of milk.

“[Small-scale farmers] are very influential on the ground and very patriotic”, says Mykhailo Amosov from the Center of Environmental Initiatives Ecoaction, an environmental organization that supports peasants. “Historically, local farmers have been part of this country’s resistance. They are responsible for food sovereignty and the liberation of their people.” Amosov also claims that Russia is deliberately targeting Ukrainian fields and agricultural infrastructure to diminish Ukrainian’s enormous agricultural capacity. Large-scale industrial farming is bearing the brunt of the war: the main damages have affected big infrastructure necessary for food production. Meanwhile, “small farmers are harder to target because they are more widely dispersed,” explains Amosov.

Wheat production is expected to be at least 35% lower in 2022, according to Kayrros data analysis. The US Department of Agriculture forecasts that wheat exports will drop by nearly half and sunflower production will also decrease sharply, bringing Ukraine down from its position as the world’s top sunflower producer since 2008/2009. The Kyiv School of Economics calculates that the cost of the war for the Ukrainian farm industry is around 4.3 billion USD, and the FAO estimates 6.4 billion USD.

But how did Ukraine become such a massive industrial food producer?

AgroPortal