Peasant communities successfully mobilized to implement the Tenure Guidelines and secure their customary rights, including those of women and youth

In Mali, peasant communities were facing multiple expropriations and forced evictions to give way to large-scale agro-industrial projects. These land-grabbing initiatives endangered peasants’ food sovereignty and their ability to feed the local population, as three-quarters of the land cultivated by peasants feeds into to domestic markets. To tackle this situation, peasant organizations joined forces with civil society organizations to fight for the recognition of their customary rights in the new Agriculture Land Law. Members of rural communities were mobilized, inclusive village land commissions implemented, and the Tenure Guidelines socialized within the communities and among members of Parliament. The result has been a re-assessment of customary land rights, which now include the rights of women and youth, and the legal recognition of a land tenure system that does not operate according to the neoliberal market rules of land ownership.

In the 2000s, Malian peasants were plagued by multiple expropriations and forced evictions exacerbated by the 2008 food crisis. In the rural municipalities of Mande and Naréna, —located in West Bamako, the capital of Mali— a partnership between the local administration and individual speculators, mostly powerful national political elites via real estate agencies and foreign investors as well, had placed communities under the permanent threat of expropriation. In total, around 800,000 hectares of land have been grabbed in Mali to make way for large-scale agro-industrial projects.

In Mandé, the municipality had to deal with the expropriation of 3,600 hectares of land by the state to resettle other communities who had been previously evicted from another area of land in peri-urban Bamako. The village of Mandé is surrounded by large sedimentary plains irrigated by the Djoliba (Niger) River where the community grows a variety of crops, from cotton to grains. The municipality is also part of the collective territory of the circle of Kati, with a tradition of community organizing that dates back to 1222 when La Charte du Manden was approved, which is often referred to as the first human rights declaration.

Faced with such massive expropriation, the community of Mandé joined the Union of Associations for the Development and Defense of the Rights of the Defenseless (UACDDDD is its French acronym), a member of the peasant movement led by the Malian Convergence against Land Grabbing (CMAT is its French acronym), an alliance of five civil society organizations: the Association of Professional Farmers Organization (French acronyms, AOPP), the Coalition of African Alternatives Debt and Development (CAD-Mal), the National Coordination of Farmers’ Organizations (CNOP), the League for Justice, Development and Human Rights (LJDH) and the UACDDDD. CMAT aimed to ensure that customary land rights were respected and secured, and that social cohesion and food sovereignty were maintained.

In the 2000s, Malian peasants were plagued by multiple expropriations and forced evictions exacerbated by the 2008 food crisis. A partnership between the local administration and individual speculators had placed communities under the permanent threat of expropriation

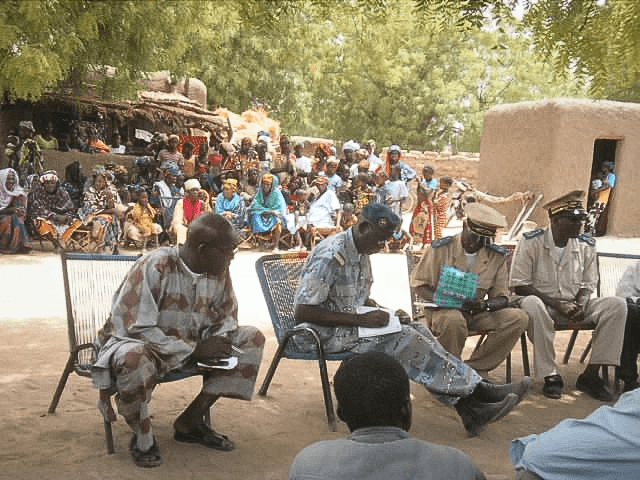

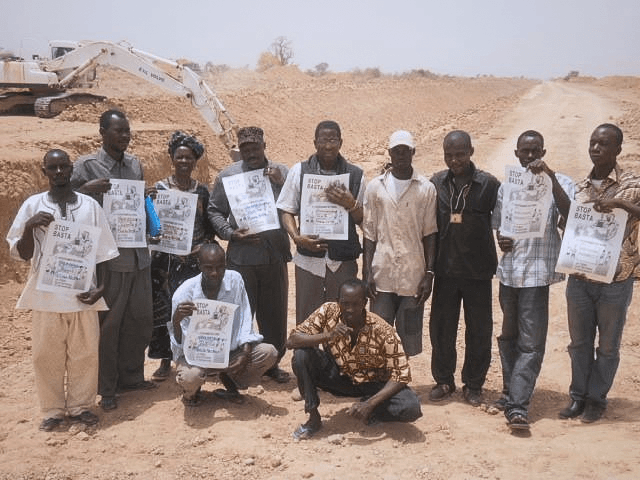

Peasants protesting land-grabs in Mali. © FIAN Internatioanal